This post is translated and editted from my own blog here

Intro

Think outside of the box

So while Linh’s complaining about his glasses,

I came up with an interesting puzzle. Look, it is normal to have myopia being a maths majored student right? Linh’s eye on the right is of 1.25 diopters, and the left one is of 2 diopters.

But that guy at the optic shop made a wrong one: the left piece is of -1.25 diopters and the right one is -2 diopters (and hence the complaints). That night, God sit down besides the sobbing poor guy suffering from shortsightedness, comforted him by handing out this magical ring. Linh was asked to drop the glasses through and he did. The glasses came through mirrored and thus, fixed.

“But, this is not mine?” - Linh uttered. “Son, this is your glasses, I mean by each and every atoms - except each and every one of them is now mirrored :)” God answered with a witty wink and disappeared.

How?

To understand a mirrored object, simply place any object in front of your mirror and observe its image in the mirror, the mirrored one is that thing seemingly exists on the other side of your mirror. Except that it is simply an optical image, not a physical object. In principle, you can’t create such a perfectly mirrored object of any ordinary object. How did God do that?

Let’s exclude answers like “Man is the f*king god, he does whatever he f*king want!”, and try to look for a feasible answer as close to what we know to be logical as possible.

Start simple

Place the glasses in front of a mirror surface \(\alpha\). What do we do? First suggestion: be simple, let’s drag each point in the glasses straight to the desired new position, after all is done, we obtained the mirror one! Assume \(A\), and \(B\) are two atoms in the glasses and \(B\) is \(d\) units away further than \(A\) from the mirror surface \(\alpha\). This implies that during the movement, segment \(AB\) must change its length. Not possible because no glasses is that flexible.

Relax the straight constraint. In other words, we are not doing translation but rotation this time. For the rotation operation, its axis \(l\) must lies somewhere on the mirror surface. It is trivial that any point \(X\) distanced from \(a\) a distance \(a\) and from \(l\) a distance \(b\), the rotating angle is \(\varphi = 2 arccos(a/b) \)

So is there any case where rorating about \(l\) by an angle \(\varphi\) gives the mirrored object? This happens only when there exists \(\varphi\) such that every points in the old glasses satisfy \(2arccos(a/b)=\varphi\). It can be seen this set of points collectively is two planes that makes with \(\alpha\) an angle \(\varphi\). Is there any possibilities that the glasses belong to such set of points? Nope. This is no different than asking a box to fit inside a paper, because only the opposite is possible.

Moving beyond 3D space

I believe we go this far just to make sure that mathematically there is no other way for the mirrored operation to be done in 3D. In the back of our head, maybe everyone is now understand that the solution lies in the 4D rotation. For anyone who hasn’t catch up quite yet, imagine a triangle (2D object) flipping itself out of the paper it was on originally, just to come back mirrored. And the act of flipping is obviously done in 3D space.

What I am doing next is some high-school-ish geometry inference to rigorously prove this result in 4D space. Why doing so, some obvious new axioms can be observed without being explicitly mentioned. Excuse some of my false denotations.

Some extra geometric objects

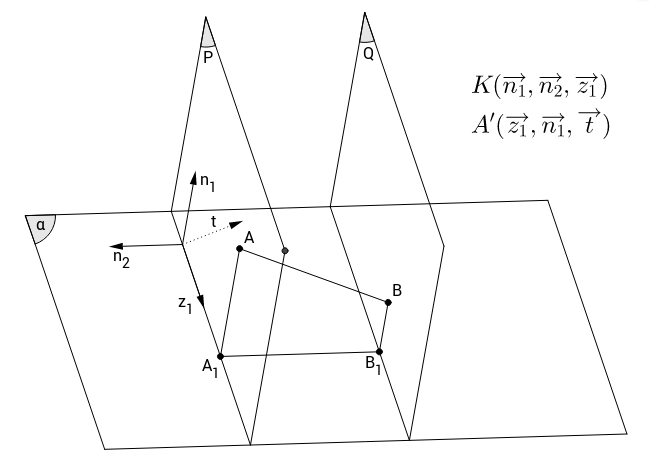

Let \(A_1\) and \(B_1\) be the projections of \(A\) and \(B\) onto \(\alpha\). Through \(A\) and \(B\) define two planes \(P\) and \(Q\), perpendicular to \(A_1B_1\), which intersects \(\alpha\) at \(a\) and \(b\) respectively (it follows that \(a//b\)).

Now the fun part.

Introduce the bases and normal vectors

Let \(K\) be the current space with bases \(\overrightarrow{n_1}, \overrightarrow{n_2}, \overrightarrow{z}\).

Let \(A’\) and \(B’\) be two spaces orthogonal to \(K\), with intersections being \(P\) and \(Q\) respectively (thus \(A’\) parallel to \(B’\)).

It is straightforward that \(A_1B_1\) is orthogonal to \(A’\).

4D-rotation = same-velocity 3D-rotations

In these two spaces, perform 3D-rotation on \(A\) and \(B\) about \(a\) and \(b\) with the same angular velocity. Since the rotation is perform about \(a\), \(A_1\) is fixed, similar logic applies to \(B_1\) being fixed.

On the other hand, during the rotation, since \(AA_1\) belong to \(A’\), \(A_1B_1\) is always perpendicular to \(AA_1\). Similarly \(A_1B_1\) is perpendicular to \(BB_1\).

Because of the same angular velocity, \(AA_1\) and \(BB_1\) are parallel as they initially are. So while rotating, \(ABB_1A_1\) is always a right trapezoid at \(A_1\) and \(B_1\) with unchanged \(A_1B_1\) (because \(A_1, B_1\) are fixed as proven above) as well as \(AA_1\) and \(BB_1\) (because rotation reserves distances to the axis),

Thus, the distance between \(A\) and \(B\) is also unchanged during this double rotation. Also when the operation is complete, \(A\) finishes at the mirrored position and so is \(B\)

Moving from A and B to the glasses

The reasoning can be generalized to any pair of points on the glasses. Now we can safely conclude that there is no contraction/retraction during the rotation, and after the rotation of angle \(\varphi = \pi\), the mirrored glasses is finally obtained.

Name the thing

The 4D-rotation above can be characterized as rotation about the axis \(\alpha\), since the set of all 3D-rotation axes to obtain mirrorization is \(\alpha\) itself. Or we can simply called it dropping through the ring.